Thoughts on Geraldine Ferraro, and Myeloma

Like many New Yorkers, feminists?, hematologists and other people, I was saddened to learn yesterday of Geraldine Ferraro‘s death. The Depression-era born mother, attorney, criminal prosecutor, Congresswoman, 1984 Democratic VP-candidate and part-time neighbor to yours truly, succumbed to complications of multiple myeloma at the age of 75.

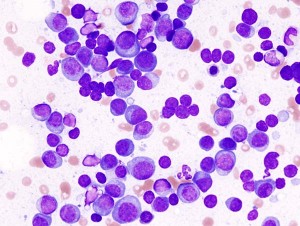

Myeloma is a cancer of plasma cells – specialized white blood cells (mature B lymphocytes) that make antibodies. Plasma cells normally develop in the bone marrow; they can exit into the bloodstream, which is why this condition is often called a tumor of the bone marrow or, occasionally, sometimes, as a leukemia. The term myeloma comes from Greek roots – muelo (which can refer to the bone marrow) and –oma, which in medical parlance has come to stand for a tumor and may derive from soma (body).

According to the NCI, over 20,000 North Americans receive a myeloma diagnosis, and approximately 10,000 die from the disorder each year. It tends to arise in older folks, and is slightly more prevalent in men than in women. According to the SEER data, in 2007 there were over 61,000 men and women in the U.S. alive with a history of this disease.

What’s notable to me, as a hematologist, about the former congresswoman is that she lived with myeloma for over 12 years: She survived with a disease for which there were few treatments available when she was on the Presidential ticket. This was partly due to luck – always a factor in cancer outcomes, as some cases are intrinsically more aggressive than others; partly due to her access to excellent doctors and good care; and, also, likely due to advances in myeloma treatment over the past two decades.

Some perspective: When I completed my fellowship in 1993, the median survival for someone with myeloma was less than 3 years. Starting around then, most specialists steered patients under the age of 65, and in some communities, older patients as well, toward autologous stem cell transplantation – an aggressive approach that’s been shown to prolong lives of patients in randomized studies. (For the record, I’ve never been convinced by those data.) More recently, old drugs like thalidomide and its fresher derivative, lenalidomide (Revlimid), along with new drugs like bortezomib (Velcade) have demonstrated efficacy in this disease.

In my opinion, what’s ahead for doctors caring for myeloma patients – and for the patients, even more so – in this next decade, is to see if these old and new pills might be better, less costly and less toxic than transplant-based treatment regimens.

A final thought on Ferraro’s care, is that it seems she benefited from the care of experts: hematologist-oncologists, transplant physicians and other specialists and subspecialists. With all the push now for more primary care doctors – who are indeed needed – her survival with what might have been a quickly terminal illness is a testament to the value of knowledgeable, well-trained physicians who keep up with developments in an evolving field.

As for the ceiling-breaking congresswoman, my thoughts are with her family now. She was a remarkable lady in many ways.

—

(all links accessed 3/27/11)

A very remarkable lady…

She was a remarkable woman in so many ways. According to Wikipedai she had a bone marrow transplant, but for the last decade was not in remission but had the disease controlled and kept on working and contributing.

A role model for all.

I find it pretty scary to think of Wikipedia as a source for a person’s medical history. (Not that it’s wrong; often, on biomedical stuff, Wikipedia seems more current than the NCI; try reading about B-lymphocytes or stem cell transplants, for example, as I did this evening.)

The problem with celebrities’ histories, as I see it, mainly has to do with privacy, besides that the story might be incorrect. Even in 2011, a woman should be able to keep the details of her illness private if she prefers to do so.

In general when I cover medical news on public figures, even if it happens I know them or their doctors, I stick to the clearly open-domain aspects of the illness – essentially what’s in (what I consider reliable) news reports, credible biographies and obits, and I link to those sources whenever possible. My point is not the details of her treatment, and I wouldn’t expound on those even if I knew them.

A post-worthy topic, Peggy. Thanks for raising it.

Elaine,

I’d love to see your take on Wikipedia as a source for a person’s public medical history (and as a source for biomedical info in general).

When I heard that Geraldine Ferraro had died, I went immediately to the NYT since I am confident that they actually report and fact-check their news obituaries. I was interviewed for the NYT obituary of my mentor, Tom Ferguson, MD, who also died of multiple myeloma (after fighting it for 15 years, following his own path):

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/24/us/24ferguson.html

Sadly, my grandmother died the same week and her news obituary in the Washington Post was lifted almost word-for-word from the notice written by my mother:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/04/21/AR2006042101965.html

Both are accurate, but one was reported & written by a staff member of the publication (the NYT) whereas the other was mostly reported & written by a member of the family (who happens to be a journalist).

Susannah, Thanks for your contribution to the discussion here. I didn’t know that about your mentor. Myeloma is a fascinating, and instructive disease –

Wikipedia constantly gets better, as I follow it, for biomedical stuff. As I wrote below/above, I worry about privacy aspects re: individual people who happen to be celebrities.