May I Call You ‘Doctor’?

Last week I considered the relationship between the Prince Albert and his speech therapist in The King’s Speech. One aspect I wanted to explore further is why the future king initially insisted on calling the practitioner “doctor.”

In real life, now, patient-doctor relationships can be topsy-turvy. This change comes partly a function of a greater emphasis on patient autonomy, empowerment and, basically, the newfangled idea that the people work “together, with” their physicians to make informed decisions about their health. It’s also a function of modern culture; we’re less formal than we were a century ago.

Patients enter the office with their own set of information and ideas about what they need. The recent Too-Informed Patient video highlighted this issue, effectively.

Doctors are human, we are painfully aware in 2011. They make mistakes and they sometimes need to have dinner with their families. They may even let us down.

When I was a young physician, my patients almost universally called me “Dr. Schattner.” I considered it appropriate, and I always introduced myself as such. After I turned 40 or so, with a few graying hairs, a higher faculty rank and more experience, I gradually changed my approach. Usually I’d say “I’m Dr. Schattner,” along with a firm handshake at the start of a visit. If a patient chose to call me “Elaine” I was comfortable with that; by then I was sufficiently secure in my authority to let people call me by my first name or by my title – whichever they preferred.

As I aged, more often, when I returned calls from patients I’d known for years, I would say “hi, it’s Elaine Schattner returning your call,” or something like that. But – and here is where the movie ties in – there were some patients who clearly preferred to call me “Dr. Schattner,” no matter what. Some were older, some quite accomplished in their fields – so much so that I felt uncomfortable presenting myself on anything but equal terms.

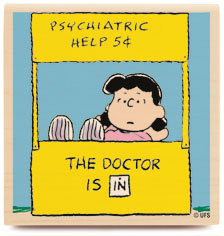

Still, most chose to say “doctor.” The reason, I suspect, is that many people want a doctor who fits the part: their idealized conception of a good, caring physician who will take care of them. For others – and these reasons are not mutually exclusive – it’s a matter of wanting to convey respect for the person who has studied so much and is using his or her knowledge to help them get well.

In the King’s Speech, Mr. Logue lacked the credentials of a doctor of any kind, which may be the reason he’s so adamant that the prince or king not refer to him as such. Why the royal character wants to call his therapist “doctor” is, I think, at least two-fold: that the caregiver would be constantly mindful of his professional duties – in the manner of the white coat, and out of genuine regard for the physician’s training, knowledge and work.

“Doctor” conveys respect. There’s nothing wrong with that, in my opinion as a patient. And it’s good, even reassuring, to find and know deserving physicians.

—-

Dr. Schattner,

I am not sure if you are being completely serious or tongue-in-cheek when you talk about this “newfangled idea that patients work together with their physician”. Is there really any other way to approach patient care?

Could expand on your comment “I was sufficiently secure in my authority to let patients call me by my first name”. What exactly do you mean by “authority” in this context?

I have a great deal of respect for many professionals who have studied and use their knowledge to help me – but only when they respect my experience in return.

You say that the patient-physician relationship is topsy-turvy. It seems as though you would like to go back to a time when the model of medicine was paternalism. If this is correct, I would be interested to know your thoughts about why that model is superior in your view to the ’empowered patient’ model.

Hi Penelope,

I am utterly pro-empowerment. “Newfangled” is necessarily tongue-in-cheek if I ever use it, which I probably won’t again.

Always I took pride in speaking openly with my patients and involving them in decisions. The point of the post is that some patients (not all) want/prefer an old-fashioned relationship and, perhaps, a paternalistic physician.